3. REPULSION (1965) October 8, 2008

Posted by 366weirdmovies in Weird Movies.Tags: Add new tag, Catherine Deneuve, Five star, Freudian, Psychological, Roman Polanski, Schizophrenia, Sexual repression

trackback

We’ve moved to a new domain: 366weirdmovies.com! Since April 8, 2009, this page is no longer being updated and has been left here for archival purposes. Feel free to read, but if you’d like to comment on this post, read our new content, or see the design improvements, please check out this post at the new site.

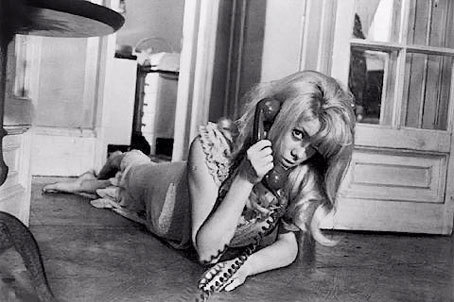

“I hate doing this to a beautiful woman.” -Attributed to cameraman Gil Taylor during the filming of Repulsion

PLOT: At first glance, manicurist Carole (Catherine Deneuve) seems merely to be painfully shy. The early portions of the film follow her in her daily routine, and we grow to realize that her mental problems go much deeper: she daydreams, she seems to be barely on speaking terms with the outside world, she is dependent on her sister (who wants to have a life of her own) to care for her, and she is repulsed by men. When her sister goes on a two week vacation, Carole’s fragile condition deteriorates, and we travel inside of her head and witness her terrifying paranoid delusions firsthand.

BACKGROUND: This was director Roman Polanski’s first English language movie, after achieving critical success with the Polish language thriller Nóż w wodzie [Knife in the Water] (1962). The relatively recent success of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) undoubtedly helped the film’s marketability, as it could be billed as a female variation on the same theme. But despite dealing with insanity and murder, Polanski’s film turned out nothing like Hitchcock’s classic; whereas Psycho was clearly entertainment first, with horrors meant to thrill like a roller-coaster, Repulsion was relentlessly tense, downbeat and disturbing, strictly arthouse fare.

Ethereal Star Catherine Denueve (who had been the lover of, and given her first break in films by, roguish director Roger Vadim) was coming off her first major success in the lighthearted 1964 musical Les Parapluies de Cherbourg [The Umbrellas of Cherbourg]. Playing a dangerous, asexual, schizophrenic woman in a role that called for little dialogue immediately after her role as the romantic lead in a musical demonstrated her tremendous range and helped establish her as one of the greatest actresses of the late 1960s and 70s.

INDELIBLE IMAGE: There are many enduring images to choose from, including the hare carcass and simple close-ups of Deneuve’s eyeballs, but the iconic image is Carole walking down a narrow corridor, as gray hands reach out from inside the walls to grope at her virginal white nightgown. (The scene is a sinister variation on a similar image from Jean Cocteau’s surrealist classic Le Belle et La Bette [Beauty and the Beast] (1946)).

WHAT MAKES IT WEIRD: Although there are several otherwordly, expressionistic dream sequences in the film, Polanski creates a terribly tense and claustrophobic atmosphere even before the nightmares come with odd camera angles and the strategic use of silence broken by invasive ambient noises. As Carole floats around her empty apartment, silent, alone, and ghostlike, ordinary objects and sounds take on an otherworldly quality. The effect is unlike any other.

COMMENTS: Polanski begins the film with a close-up of a woman’s eyeball, an opening that is reminiscent of the first shot fired in the Surrealist film revolution. Later on, a straight razor features in the story prominently, strengthening this connection. And, of course, the famous scene of the hands morphing out of the walls inevitably brings to mind the other iconic Surrealist film image: Cocteau’s candelabras.

But despite the nods to his influences, by nature Polanski isn’t a surrealist, but a Symbolist. In Repulsion, Polanski weaves images masterfully, but although they may be obscure, they are never incongruous and irrational juxtapositions, like the Surrealists sought. After opening credits play over the shot of the eye, the next image we see is a close-up of a woman’s cracking facial beauty mask. Cracks recur throughout Repulsion, and obviously symbolize Carole’s deteriorating mind. Early on, Carole looks at a developing fissure in the apartment wall and muses, “I must get this crack mended”; much later on, a crack in her bedroom wall breaks open and draws her into a particularly nasty nightmare. Select symbols, both visual and auditory, reverberate throughout the film in a way that creates a subliminal narrative that, in an important way, is more important to the story than the minimalist plot. Besides eyes, razors, and cracks, we also catch echoes of the sprouting potatoes and a hare’s corpse, along with the ticking clock, the dripping faucet, the street band with the spoon player (Polanski’s cameo appearance), the doorbell and phone (which sound exactly the same), the tolling bell and the laughter rising from the yard of the nunnery. That the first shot of the narrative should be a crack appearing on a woman’s face telegraphs Polanski’s story about the crumbling of a woman’s personality.

The imagery and symbolism aren’t the only things that are masterful about Repulsion. Critics have correctly noted Polanski’s use of sound, which expertly balances silence and atmospheric noise with judicious bursts from the alternately swinging and dissonant jazz score. The superlative black and white cinematography and can’t be forgotten, either; there are times when a shot of three aging potatoes looks like a grayscale Max Ernst landscape. The photography often has a way of transforming the ordinary into the strange and unfamiliar, a visual metaphor for the way Carole sees the world.

But the single most important element that makes the film a success is the magically glacial performance of Catherine Deneuve. She is in the screen almost all the time, and says almost nothing. In fact, except when she is terrified, she is frequently emotionless, staring off into space in her own dream world, totally blank faced and inscrutable. And yet, watching her, it seems impossible to believe that other actress could have captured Carole’s insanity and made it seem plausible. Deneuve must have known and observed a schizophrenic during her youth; she perfectly captures the subtle tics, the chewing on the lip, the spastic scratching (so unselfconscious and unfeminine), the swiping about her face as if swatting away invisible insects.

It doesn’t hurt that the face is classically beautiful, of course; casting an ugly actress in the role would have made the movie unbearably repulsive. The tension between Deneuve’s exterior beauty and the grotesqueness of the world behind those eyeballs is the contrast that compels our interest.

In the beginning of the movie, we observe Carole entirely from the outside. We are given no clue why she acts so detached. We simply study her as a beautiful curiosity. We see her the way her co-workers and her would-be beau does: she seems shy, distracted, perhaps even dull and flighty, but at the same time mysterious and vulnerable. But when her sister leaves on vacation and Carole is left alone in the creaky, haunted apartment, our focus suddenly shifts from looking at Carole to seeing the world through her eyes. Our first hint that we have entered a new world is when, along with her, we catch a glimpse of a man’s figure in the mirror–a man who couldn’t possibly be there (and in fact isn’t, when she turns to look). Soon after, we are thrust into her (literal) dreams and nightmares. And things grow increasingly worse from there, until we the viewers struggle to tell what is really happening anymore. We find ourselves travelling with her down that long dark corridor with the grasping hands.

There are a few things to criticize about the film, although none are serious enough to keep Repulsion from earning its five star rating. Polanski lingers a bit too much over the setup. Things don’t become really interesting until the sister leaves on vacation at about the 40 minute mark. This is artistically justifiable, as the perfectly innocent items Polanski introduces in the early reels-the cracks in the wall, the rabbit, the dripping faucet, the foolishly misguided suitor-will recur with a sinister cast once Carole’s break comes. But the slowness of the opening scenes will unfortunately keep many from actually experiencing the film.

Another frequent criticism is that, true to its name, Repulsion is relentlessly unpleasant. It creates a tension that is never pleasantly relieved by the triumph over evil; Norman Bates is never defeated, Carole never escapes herself, the audience is never rewarded for allowing their nerves to be grated. This is true; Repulsion isn’t entertaining. But what it does, in taking us unflinchingly inside the unpleasant world of madness, it does better than any other movie. Catharsis would have rung untrue in Repulsion, and blunted its impact. If there had been a single artistic slip, the film would have sunk from being an unforgettable classic into being just an interesting but disturbing experiment. We don’t want every film to be like Repulsion, but we can be glad that at least one exists.

The last criticism is my own, and it goes to the heart of the film. The objection is there in the very title: Repulsion. Too much is made of the idea that Carole’s illness is related to her fear of men, her sexual repression, and her possible history of childhood sexual abuse. The audience is beat over the head with this idea, from Carole’s dreams of rape to her obsessive tooth-brushing after her suitor manages to steal a kiss to the fact that she only seems briefly normal when she interacts with either her sister or her lone friend, a female coworker, outside the presence of men. Many interpret the final shot-a camera pan to a family photograph that lingers on the face and eyes of Carole as a young girl, sporting the same dead-eyed, distant stare as she does as a young woman-as a hint that it is childhood sexual abuse has caused Carole’s repulsion, leading eventually to obsession and madness. The idea of Carole’s “repulsion” to a past rapist seems offered as a sop to those who lust for a solution to the puzzle of her madness, as well as an excuse for Polanski to explore the dark side of human sexuality that has always fascinated him (sadly, in real life as well as in art).

Repulsion is, in fact, the most accurate depiction of schizophrenia ever put on film (there wasn’t really much competition in this field, until 1993’s Clean, Shaven). This is true whether Polanski and Deneuve knew the name of the disease they were recreating or not. It is unfortunate that Polanski chose to focus on this “solution” to Carole’s plight, because the idea that sexual dysfunction was the root cause of every psychiatric disease known to man or woman-from frigidity to nymphomania, from fear of heights to schizophrenia-is a now-discredited relic of then-trendy Freudian psychology. (Many psychiatrists now doubt that there is much link between schizophrenia and childhood sexual abuse). Sex is central to human existence, but it doesn’t hold quite the monopoly on the unconscious that Freud, and certain 1960s movie directors, believed.

Carole’s repulsion towards men is more interesting as a symptom of her condition then it is as a cause. Her disorder goes deeper than a mere fear of men. When she literally barricades herself inside her apartment-inside her own crumbling mind-she is not merely hiding from an outside world where every construction worker on the corner is a potential rapist. She is hiding away from humanity, from reality, from existence itself. Schizophrenia-literally, “splitting (or ‘cracking’?) of the mind”-is terrifying because it is a pathology that arises spontaneously, mysteriously, without pat explanation. Our desire to find a “cause” for it, to understand and master our own fears about our sanity, is a sign of our own mental infirmity.

Fortunately, it isn’t necessary to embrace this psychoanalytic interpretation of the film to praise it. Polanski has left the root of Carole’s illness ambiguous enough to allow us freedom to ignore his Freudian blunders. It is possible to see the final image of the dreamy waif merely as evidence that Carole has always been this way: that she was singled out randomly to live out a brief life of torment. In the end, the source of Carole’s irrational terrors isn’t crucial to the movie’s impact. It’s the stark document of what happens in her during those seemingly endless nightmare days and nights, barricaded away from the world, that sticks with us, and makes us afraid. The possibility that our own minds may betray us and drag us down to Hell is a far more frightening than any psycho-slasher in a hockey mask ever could be.

WHAT THE CRITICS SAY:

“It’s clinical Grand Guignol, and the camera fondles the horrors… Undeniably skillful and effective, all right-excruciatingly tense and frightening. But is it entertaining? You have to be a hard-core horror-movie lover to enjoy this one.” -Pauline Kael

IMDB ENTRY: Repulsion

DVD INFO: The Anchor Bay release is the superior version, and contains commentary by both Polanski and Deneuve as well as a featurette on the British horror film. Many have complained of poor picture quality (and an unforgiveable pan-and-scan aspect ratio) on the Entertainment Programs release.

[…] [Polanski Unauthorized]: The controversial director of Repulsion (and other weird flicks) gets his own limited-release biopic. The trailer makes it look like a […]

[…] as Eraserhead (in regards to its ability to evoke the nightmarish quality of everyday objects), Repulsion (disintegration of the mind of a sexually repressed woman), and even Apocalypse Now (the shot of […]